Don Simpson: From Anchorage to Bel-Air

Independent article by David Thomson on the life and times of Hollywood’s most ambitious film producer Don Simpson.

Where do we begin? How would Don Simpson have begun? Try this: we are in Anchorage, Alaska, and it is 1953, the early days of the Eisenhower administration. We are in a bathroom. We will need a genius on decor, someone who can get the resemblance between a very neat and tidy prison cell and a bathroom from lower-middle-class Anchorage, Alaska, in the early years of the Eisenhower administration. Are you with me?

There is this little boy, eight years old, with black hair and one of the fiercest looks you ever saw – a face that is determined to believe. And he is sitting on the edge of the bath, staring at himself in the mirror, and he is repeating this phrase, in rising anger or panic: “I am Donald Simpson, I am Donald Simpson…” Then the kid stops. There is a moment of suspension. The look on his face eases. He smiles, and he tells the mirror, “And You Are Not!” Like the little boy has seen the light.

Cut from one face in the mirror to another. It is some time late in the night of 18 January or early in the morning of 19 January, 1996. We are in the bathroom of a Bel-Air mansion, and this guy, Don Simpson, is sitting on the john. He seems half asleep. A book slides off his lap – the latest biography of Oliver Stone. The guy’s eyes open. This is a huge man, not tall, but vast in the belly, the chest, the shoulders and the head. You feel as if his head is a balloon that has been blown up by the body to a point close to bursting. This hulk is horribly out of shape – 250lbs – but we should recognise the same fierce, desperate look from the little boy’s face in Anchorage, Alaska.

The fierceness has not abated, but now there is a grin on the face that seems to understand that even ferocity is just an act. And he starts to whisper to the mirror, “I’m Don Simpson…” until some spasm goes through him. He groans. His hands reach for his heart. And he begins to slide off the john onto the marble floor. But he gets off this last, gasping punch-line: “And you’re not!”

He’s dead on the floor, this short, huge man with his bare bottom pointing up at the soft lights. This should be an amazing bathroom, and on the vanity there are rows of bottles and medicines like make-up on the table in Joan Crawford’s dressing room. It is like a pharmacy.

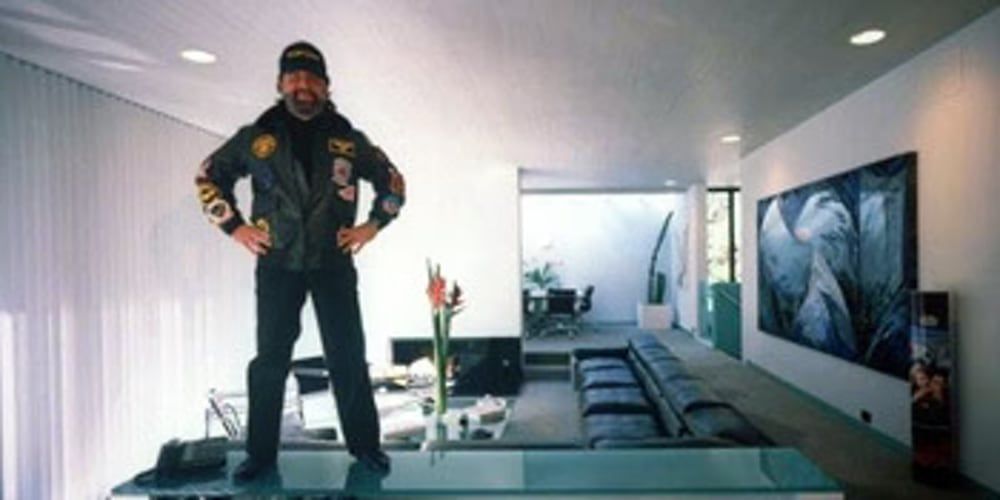

Boom! We come out of this with the opening title: The Don Simpson Story. And behind the credits we run a montage of the great days of Don in Hollywood – we see clips from Top Gun, Flashdance and Beverly Hills Cop, and glimpses of Don with very famous people at the premieres, and we get a sense of this strutting gamecock all dressed in black, because the montage is running backwards, so Don is getting slimmer and younger, with the middle-aged slob made over and back into the sleek gangster as handsome as a Red Indian brave. And though the film is going in reverse, there’s this terrific rock score pounding forwards so that we feel the going backwards is positive and desirable. Snap cut. Black out. We’re into the picture.

As I see it, Anchorage in our movie is this fantasy place where it is snowing, and there are canyons of piled-up snow on the street. I would not even mind if we had interiors with snowbanks against the walls. And the people wear heavy clothes, like parkas, indoors, because, God, it is so cold. And God is the cold, because these are Southern Baptist fundamentalists living in Anchorage – we don’t even try to explain this displacement. And the kid, this little animal Donald, he goes around the house naked whenever he can, because he defies the cold. And his parents are beating him for it, and he has to go to church three times a week. But in church he can’t keep his eyes off the grown women, and as he watches them his eyes seem to just burn their clothes away. We can do this a la Fellini, right – quick, funny, pungent, cartoonish.

And Donald’s father says to him: “Just thank God, Donald, that God didn’t kill you today. Because we are all born evil, nasty, dirty people. But if we make it in this life, God will give it all to us in the next. And if we don’t make it here, we will burn in hell forever, so there is no end to the burning!” And the boy’s eyes are angrier still, thinking about this lousy deal.

Then we are in the church again, and while the congregation is praying, Donald gets up and walks across the aisle to this grown woman who is sitting there in her early-Eisenhower-administration underwear, and Donald begins to touch her up. Then he is in a cell – which is the pastor’s room – and the pastor is telling him he must purge all thoughts of lust from his head and close his eyes. He passes his hand over Donald’s eyes, but they stay open. And the boy tells the pastor he can’t stop these thoughts. So the pastor warns him, “If you think about it beyond this moment God will strike you down.”

And we see Donald look up and around, like a kid searching for a bat in the rafters. And you know he’s still thinking the forbidden thoughts. And the pastor hits him. Cut! We have this huge landscape of snowy Alaska, with a road that is empty except for the figure of a boy who is trudging away into the distance that is the rest of the world, and the future, and Hollywood!

Now, perhaps you’re protesting that this is hardly decent or properly factual for an obituary. Let me make the case that it’s the way Don Simpson would have wanted it, that it balances the dream and the facts in just the way Don practised. All the things I quoted are from Simpson himself as he reflected on his early life in James Toback’s documentary film, The Big Bang. When he did that, in 1990, Simpson was a very big wheel in Hollywood, but there he was, happily telling stories on himself. Why? You have to wonder. Most of Hollywood’s powerful people wouldn’t confess to the truth under torture. But Simpson wanted to be in Toback’s movie because he’s always had this driving ambition to act. It hadn’t worked out, so he’d turned the desire aside: he played himself; he was “Don Simpson”, and we weren’t. That’s the best reason for the opening I’ve given you. But now it’s time to be a little more critical of Don’s movie.

He didn’t walk out of Alaska as a child. The walk is too long, and Don always wanted such staples as functional bathrooms. That he was a very bad boy in Anchorage is not in doubt. But he left at the requisite age to attend the University of Oregon, where he was a prize student. Although his subsequent films give no hint of this, Don was a bit of an intellectual: indeed, he would sometimes say that he hired in call girls for the weekend so as to discuss Dostoevsky – once the formalities had been transacted.

So he is out of university some time in the late Sixties, which is about as close to the Baptist hell as we’re going to get – unless there’s a meltdown in every last vestige of order. He had reached San Francisco, where the attempt at meltdown was being earnestly pursued. He was working for a showbusiness advertising agency and running publicity for the First International Erotic Film Festival. This is important, because – despite the Dostoevsky – Don had a very basic attitude to the movies: he was for sensation, speed, violence, nudity, getting the point straightaway, and things the public had never seen or done before.

Don got his Hollywood opportunity thanks to an executive at Warners named Joe Hyams. Joe has since acquired fame and prestige for being “vice- president for Clint” – he is the person at Warners who keeps Clint Eastwood happy. Hyams has enormous wit and charm, both of which stem from the way he talks like a supporting character in a Billy Wilder film. He is always on, always sounding like a smart screenplay. This isn’t, any longer, an act. It’s Hollywood entering the nervous system; it’s the way picture people always seem to be in their own movie. This made Don. He saw that he could be himself and be fictional at the same time. The role he chose was that of tough, self-destructive candour, the kind of macho boast that is its own mockery. There was no need to be himself, or find himself – he had his act down.

At Warners, for several years, Don was in marketing on youth-exploitation pictures. Then, in 1973, he was stolen by Paramount – these were the last heady days of that studio, when it was run by Robert Evans first, and then by Barry Diller and Michael Eisner. Don was their prize dog: they loved his flamboyant fierceness; his exuberant routine of looking to lay every woman he met; his confidence that a movie could be expressed and described in a couple of sentences, maximum; and his enormous capacity for fun, money, debauchery and drugs. More or less, the average Hollywood tycoon prefers to be discreet about that plunder. But Don was an animal, and the suave masters in silk suits were tickled that he was so naked, so acting out with it.

He helped to write and played a small part in the action movie Cannonball, but he was more importantly a thrusting new executive, becoming more powerful at Paramount with every quarter. He figures occasionally in Julia Phillips’s book, You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again. She sees him as a relentless, ape-like, funny, attractive and avid cocaine-user, a weird mix of stupid and smart, right brain and left so at war you could see the zip in the middle of his head. They sort of have sex in the way of people who are talking dirty to feel out the chance of doing business:

“When we get back to the hotel, Don is still wired from the Redford evening, so we have a nightcap in my room. We get into some heavy necking, but he is very uptight about my married status. I say something corny, `Don’t make me beg,’ but the farthest he ever goes is down on me … After this quasi-sexual encounter, he feels very free about expressing his preferences, which seem to revolve mainly around turning women over and fucking them in the ass. He talks about angry fucking, and I am grateful we never get to intercourse, because I don’t think I’d like it very much his way. We stay tight friends, but it is by silent mutual agreement that there will be no more sex.”

Now this happened when Julia was bigger in the business, because of The Sting, Taxi Driver and what was going to be Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Bigger than Don. But Don was rising. And by 1981, he was president of worldwide production at Paramount. You have to be entertained by that kind of cartoon title, but you need to marvel that an explosion waiting to happen like Don got to be president of anything – unless it was pissing on the culture, or turning it over.

Pissing time was the Eighties, which everyone more or less, in historical retrospect, regards as the worst decade Hollywood has ever had. Until this one. Don was running Paramount (under Diller still), and this was a time of An Officer and a Gentleman, Star Trek and Friday the 13th. But Don was a little too flagrant to be a president; there was too much cocaine in plain sight for the comfort of his superiors. So Don went into independent partnership with Jerry Bruckheimer, a producer who had helped assemble American Gigolo, Thief and Cat People. They made an intriguing team, with Bruckheimer the quiet, polite cop and Don the shit-kicker who would go in for public lamentations about the softie and the stooge Jerry was, and how Don was the man, the one behind their success. But remember, Hollywood loves its acts, and it was the idiot Costello was dominated Abbott, and it was Jerry Lewis who looked after business and worked out routines for the “sophisticated” Dean Martin. Don actually never got his name on a hit until Bruckheimer came along to tidy up around Don being Don. But they got on, and Paramount still released their pictures, with the boys getting a sweetheart deal so that on all their pictures Simpson-Bruckheimer got a cut on the first gross dollar. That is the only way to make real money, and to guarantee yourself against the pictures being duds.

But their movies worked. In the next few years, they made Flashdance, Beverly Hills Cop, Top Gun and Beverly Hills Cop II. None of those films is going to be preserved by the Library of Congress, but all of them, for a few weeks, were things “everyone” wanted to see. They were also Simpson-Bruckheimer projects, the ultimate in high-concept, nutshell movies: Flashdance – “It’s MTV on the big screen”; Beverly Hills Cop – “Streetsmart black cop from Detroit finds himself in Bel-Air”; Top Gun – “Rock’n’ roll kids in jet planes”; Beverly Hills Cop II – “He does it again”.

Days of Thunder was the next one up, and that was “Top Gun in racing cars”. But Flashdance, for instance, grossed nearly $100m domestic, and then there was foreign and video to come. Sometimes the sums of the money on the cheques for Don and Jerry were longer than the nutshell selling lines.

Something began to go astray during Days of Thunder. Don played a small part in that movie – an Italian race-driver – and the same year he acted in Young Guns II. “Being Don” was pushing him, making him more aggressive, more cocksure, more assertive. He got into prolonged disputes with star Tom Cruise and screenwriter Robert Towne over the script for the film. And he was branching out with drugs.

For years, Don Simpson had been a cocaine freak, without apparent problems. He had it under control. The blow just kept him firing and moving. But years of cocaine can often lead to paranoia, delusions and depression. More to the point, in 1990, Don was 45. For 20 years he had worked very hard, which in Hollywood is often a matter of keeping up the show of work, of meetings, taking calls, making deals, when lesser people are dropping. Don didn’t drop; he was always there, still grinning, in the poker of business. He might be down on someone and still haggling over points. He ate – ice cream, peanut butter, junk food – and he did cocaine; and he screwed hookers. He was never married, or close to it. But he had a well-earned reputation for funding orgies, and word got out – it’s a word-of-mouth town – that the orgies were sadomasochistic. He liked to impose pain, indignity and humiliation on women; and then he liked to go away as their friends.

After Days of Thunder – which didn’t do as well as its ruined budget required – Don stopped. He started taking a lot of prescription drugs, antidepressants, uppers and downers. His weight began to shoot up, though some thought that was because of new, untested growth hormones he was taking. Their alleged function was to improve sexual potency as the natural effects of age set in. But they also left him bulkier, bloated and ashamed of himself.

Jerry Bruckheimer was in deep distress; he loved Don – some said he was the closest Don ever came to having a wife, albeit an abused one – and their business was foundering. He helped put Don in detox clinics, but nothing worked. In 1994 and ’95, Bruckheimer mounted some new pictures, and Don helped when he could. The movies did fine – Bad Boys, Dangerous Minds, Crimson Tide and a last one, still to come, The Rock, in which Alcatraz prison is occupied by terrorists and the good guys (Sean Connery and Nicolas Cage) have to break in. That’s a Don movie for you: how do we get into Alcatraz?

But Don was seldom there on the set. He was becoming more reclusive. He had stopped returning calls. He was looking for help. One possible source was Dr Stephen Ammerman who said he thought he had an answer for Don. Then one night in August 1995, Ammerman called Don and invited himself up to the Simpson house on Stone Canyon Road. Simpson said come on by, but he was going to sleep. The next morning, Don got up and found Ammerman dead by the pool house. There was a syringe nearby. Death was due to an overdose mixture of valium, cocaine and morphine. So Don was minus his key doctor.

He had check-ups and he got severe warnings. His heartbeat was so irregular that he risked Sudden Death – which wasn’t just a title. It could hit him as he woke up, when he ate, or if he went to the bathroom. That’s how it happened, with Don doing his best to take a shit after a five-hour telephone call. Was he talking to the mirror, or is that just a movie? Who knows, except that by the morning no one was Don Simpson anymore.

The loss of a life affects us all – right? Or is that just a line from one of those smash-hit, forgotten-next-week movies that Don was expert at? Hollywood went into shock over Don. There was a huge wake at Morton’s restaurant, where the guys told terrific, hilarious stories about the things Don did and said and screwed. John Gregory Dunne wrote a dreadful, sentimental piece for the New Yorker. There were solemn investigations of the “tragedy” in other magazines. Don was in the list of honoured dead on Oscars night along with Gene Kelly, Ida Lupino and Louis Malle.

Hollywood is a funny town, or maybe less a town than a club that protects its members and their illusions. Don Simpson, I think, was a cold, brutal, empty-hearted pig who put on a huge act about being one of the guys. If he’d been a teacher, a cop, a politician or a member of a serious criminal organisation, his lifestyle would have had him thrown out. But all he did was make junk that appealed to the escapist fantasies of millions of guys. He was Don Simpson, and he deserved pity and contempt. But don’t be surprised if in a few years he’s back on screen, looking like Stallone, in something called Dark Genius, or just The Don. It’s a hell of a part – all flash, no character.