Orson Welles: Razing Kane

In a 1996 Los Angeles Magazine adaptation from a controversial new biography by David Thomson, the director of the greatest film of all time is revealed not as a martyr to Hollywood but as the auteur of his own failure.

He was alone on the night of October 9, 1985, which is not the same as lonely. He was not well or strong. He was too heavy, he has diabetes; his heart was exhausted. He had his own mother lode of disappointment, rejection and failure. But that fragility is not the same as self-pity or even melancholy. He had always been the most important person in his own drama. His “failure” was a sustaining tragedy – his thing, his song. He was not a possessive man in obvious ways, not with money or people. He let those things slip through his hands. But some airs and attributes he kept: command, the magician’s power, the rights on self-destruction.

He was uncommonly lucid about himself and acted on it. He was not like others. They could not be like him. Why are there so few of you, he has taunted audiences, and so many of me?

He had known great friendships, he had moved men and women with his anecdotes, laughter and heady company – yet something in him was resistant to giving up loneness, something implacable in his soul that depended on being isolated, whether in Xanadu or a relatively modest place in the Hollywood Hills.

He dies alone that night, sitting in his chair, typing up script for things he meant to film the next day. In the early hours, he called his friend Henry Jaglom, a director born two years before Citizen Kane opened. His best friend? There were arguments over that. Some said that for years, Jaglom had made a habit of recording his conversations with Welles. Some said Welles had never known about the recording – he’d been set up, bugged, like the character he played in Touch of Evil. Some said Welles had discovered this and felt betrayed.

Perhaps. But Welles knew Jaglom – he’d had years to look into the face of a smart, talented, rich, insecure and very needy man. He saw how he was a model and a father for Jaglom, a god who might grant him admiration or fellowship. And Welles was fascinated by neediness in others – he could see it from a distance, like connoisseur. Moreover, he had been in the business of being betrayed all his life. He used it as a way of always being right, superior and alone.

He wasn’t a simple or straightforward person, not necessarily a nice man – no one to sentimentalize. Still, he left a message on Jaglom’s answering machine in the middle of the night: “This is your friend. Don’t forget to tell me how your mother is.”

When Jaglom woke up, the friend was dead – which surely adds to the magic of the message. There’s no reason to think Welles intended the sentences as last words. But he had a habit of leaving words hanging in the air, pregnant yet not quite born – rosebuds. Put it this way: He talked like a man who was forever uttering last words and leaving us to wonder whether rosebud was the promise of sweetness and flowering or a knob of youthful hardness. He had been wondrous and distant from birth, a prince and a devil, truly a director, someone who shaped everything, not least his “failure.”

No one had ever given Orson Welles so large and irremovable a “no” before 1942, when he was 27 and he lost The Magnificent Ambersons. There were parents who adored him – perhaps worshiped is a better word, for it conveys an obligatory distance. But there’s no suggestion anywhere that they ever dreamed or dares to say, “No, don’t play in the snow in just that sarong,” or “No, don’t make up those ugly words to go with Verdi.”

Richard Welles was an occasional inventor in Kenosha, Wisconsin, a dandy – his son would remember spats that were white, dove gray and mauve. He was also a drunk and a gambler who had his own brand of cigars. His son later claimed his father had designed an airplane and broken the bank at Monte Carlo. His wife, Beatrice, was a concert pianist until family hardship made her take up typing. She was ill often. According to her son, she was also a champion shot, a skilled jockey, a suffragist, and a scholar of East Indian literature.

One day, Orson’s story went, he had been practicing scales with a teacher when he stormed out, saying he would kill himself. He climbed out a window – this was the Ritz in Paris – and perched himself on the railing. But when the teacher fetched Mrs. Welles, she said, “Well, if he wants to jump, let him jump,” No one ever said, “No.”

By the time Orson was 15, both his parents were dead. The next year he went off to Ireland, alone, on a painting holiday. But when he arrived in Dublin, he offered himself to the Gate Theatre as providentially available young actor – “Orson Welles from America.”

His debut was noticed but was certainly not providential. He went to Spain for a while, writing pulp fiction and watching brothel life. Then, in the late 30’s, he took on New York. He staged his Harlem Macbeth, his modern-dress “Julius Caesar” and that sublime schoolboy trick, “War of the Worlds.” By then, there no need to pay his dues or eat Hollywood’s shit. He was Orson – he would eat steaks and cheesecake.

It worked, of course. RKO gave him carte blanche, and he made a film that, 55 years later, still looks the greatest of American films – as well as hid dead end. “Citizen Kane” was the first movie in America that needed to be seen more than once, that aspired to the depth of literature and music, that was also a black comedy about the fatuity of success, money, power and happiness – those bright apples in the eyes of Hollywood, FDR and William Randolph Hearst.

Not that Kane was simply about Hearst – Welles was far too self-centered for that. Kane’s character was based more on Orson: his charm, energy, self-destructiveness and solitude. After Kane, Welles knew he commanded a new world, but what next? He thought of politics – there’s little doubt he dreamed of being President. But that’s no job for one so easily distracted, and Welles’s gluttony, despair, solipsism and cruelty to others began in the fickle boredom of a genius who had no ordinary life.

So, by his contract, he made another film for RKO, “The Magnificent Ambersons,” based on Booth Tarkington’s novel. It is a story about love and family – and that sturdy Midwest life at the turn of the century, before progress spoiled it. As such, it is about all those strands of real life that Welles had seen – like a traveler on a passing train – without ever really possessing. It was the dark past where he might have been loved, and been able to love others.

Ambersons was an even greater film than Kane, an authentic tragedy – not mere “genius,” but human nature and loss help up to view. By early 1942, the film was shot and pretty well cut. But then, with all the boring chores of post-production waiting for him, Welles took off for Rio, and Carnival. He said he had to; it was for the war effort, to foster good relations with Latin America. He said he’d been asked – or told – to go by Nelson Rockefeller at the Office of Inter-American Affairs.

It wasn’t so. RKO had to pay for the whole thing – the government was no help. Welles went to get away, and for the women. It was a terrible gamble, a way of finding out just how powerful he was and how reckless he could be.

In his absence, the studio tested the film, and there were enough idiots who said it was too long, too sad, too serious, too dark. So, RKO took the film away, and the trusted people Welles had left behind were powerless to resist. RKO cut Ambersons from two plus hours to 88 minutes, ordered a “happy” ending and ensured a ruined- even lost – picture. His people begged Welles to come back, but Orson was having too much fun.

He had shot miles of film at Carnival, then began restaging the event to get more – all for a vague, episodic project called “It’s All True.” He was revealing Rio as a place where blacks and whites danced together – and much more. While at a nightclub to shoot chorus girls, Welles whispered in his manager’s ear, I’ve fucked that one... that one... and that one.” At the same time, there was a plan to re-create a heroic, 1,500 mile raft trip made by poor fisherman from northern Brazil to dramatize their lot. But during filming, the leader of the group drowned. “It’s All True” was never completed – and the footage went into limbo for decades.

As the studio began a campaign to discredit him, Welles’s associates worked to outflank them. Go back to Washington and get acclaim there, they cabled: “If somebody will come out with a thank-you statement, you will return a conquering hero.” But no one in Washington ever did. They regarded the whole Brazilian enterprise a typical Hollywood indulgence.

Welles made an inane tour of Latin America, kicking up stinks in Bolivia and Peru when he wasn’t greeted by U.S. embassy officials of sufficient status. By the time he returned to Hollywood, it was too late. Then, for the rest of his life, he told how RKO had coined the slogan “Showmanship instead of genius” so “they [could sell] their product on the basis that they no longer had me.” It was a grievance that shows how much genius meant to him, and how confused he was about his own showmanship. He took an air of being wronged or misunderstood that ill befit a showman. It may have been the beginning of the great load of flesh he could never lose.

Bit by bit, in the late 40s and 50s, Orson Welles gave up America and let the idea gather that it has dismissed him. There was a touch of retribution and humiliation in the process.

Of his vices, he admitted to melancholy and sloth. Gluttony, too, he had to accept, and with mixed feelings: “It certainly shows on me. But I feel that gluttony must be a good deal less deadly than some of the other sins. Because it’s affirmative, isn’t it? At least it celebrates some of the good things in life. Gluttony may be a sin, but an awful lot of fun goes into committing it. On the other hand, it’s wrong for a man to make a mess of himself. I’m fat, and people shouldn’t be fat.”

Tynan also asked about women. Welles had always had affairs; they tended to be with exotic, dark women, often those he was working with. But nobody ever got the impression they mattered much. Welles liked to seduce, but he seldom had lasting ties. (He had had three daughters, but only Beatrice lived with him very much.) His third marriage to Paola Mori had lasted but was not much more than a formality.

As he worked on “The Survivors,” Peter Viertel learned that Paola herself was having an affair, with an airline pilot. She was anxious whenever this man was away, and Welles saw the strain. She should probably have an affair, he confided to Viertel, they’re so relaxing.

But on and off throughout the 60s, Welles was himself engaged in the most significant love affair of his life. On a trip to Yugoslavia while making “The Trial” in 1962, he met a young woman name Olga Palinkas. She was dark, beautiful, warm, funny, smart – and at least 20 years his junior. She worked on TV in Zagreb, but it was said she was also an actress, a writer and a sculptress. Gradually, something of Welles’s mythmaking was added to the young woman’s considerable personality. She was, he said, half Hungarian, and another name was fashioned for her: Oja Kodar. One observer remarked on the deep impression she made on Welles: “She doesn’t need him to exist. He worships her because it’s the first intelligent woman he has had in his life.”

By the late 60s, Welles and Kodar were seen openly together. In 1967, onboard a yacht off the coast of Yugoslavia, he filmed parts of a movie called “The Deep,” a thriller starring Welles, Kodar, Jeanne Moreau and Laurence Harvey. In the space of two years, with several trips to Eastern Europe, much of the film – or most of a film – was shot. But there were gaps, and when Harvey died in 1973, there was still material involving him left to be done. Those who have seen passages of the film suggest it is conventional at best. There is the possibility that “The Deep” was always a front for the developing affair with Kodar.

Paola made no attempt to interfere. Not that her husband was an easy man to trace. In the late ‘60s Welles’s life was teeming with projects and prospects. He began to be in America more, if only to appear on “The Dean Martin Show” – he debuted there in September 1967, singing “Brush Up Your Shakespeare” with Dean while doing one of Shylock’s speeches from “The Merchant of Venice.” Twice, he helped novice directors by playing magicians in their first pictures: Brain De Palma’s “Get To Know Your Rabbit” and Henry Jaglom’s “A Safe Place.” He also played General Dreedle in Mike Nichols’s “Catch-22,” one of many films he had wanted to make himself.

While shooting “The Deep,” Welles talked to Kodar about a real collaboration, “The Other Side of the Wind,” an invocation of the ineffable that hints at the elusiveness of the project, which became a rambling, ongoing party as much as film.

It had begun years earlier in Spain, as Welles watched from a distance the progress of the elderly Hemingway following the bulls. The great man was surrounded by his cult and the clutter of lunches that always lasted until dinner. Welles was amused, even touched for he was not entirely averse to that kind of entourage himself. He was also tickled by the notion of the old artist repeating lines of his characters from books he could no longer match.

There was a script, “The Sacred Beasts,” in which the beasts were the bulls, the titans of art and the bullshit brigade. Kodar had then added to the stew – for in her sharp but sympathetic way, she may have had a clearer eye for the subject. Welles elected to make the Hemingway figure a movie director named Jake Hannaford. But Kodar had another slant on him: “[He] is a man who is still potent – it’s not that he is impotent – but gets a real kick from the idea of sleeping with his leading man, sleeping really with the woman of his leading man. So he is not a classic homosexual, but somewhere in his mind he is possessing that man by possessing his woman. And at the same time, he is very rough on open homosexuals.”

With Kodar’s changes, there were now two scripts packed into one. On the other hand, it’s also possible there was never really a script so much as the idea of a film. Welles asked John Huston to play Hannaford, and he agreed. But no script was delivered.

Then one day in July 1970, a young cameraman, Gary Graver, with just a few exploitation movies behind him, heard that Welles was at the Beverly Hills Hotel. He called up but was told the director had left. Graver went home to his apartment, where the phone was ringing. “Get over to the Beverly Hills Hotel right away,” said the familiar voice. “You’re only the second cameraman who has ever called me. The first was Gregg Toland [who shot Kane].”

At the hotel, Graver was required to shoot some tests for “The Other Side of the Wind” – and was hired. Within days, Welles was calling him Rembrandt. Graver would be Welles’s close associate for the rest of his life, a modest talent plucked from nowhere. The cameraman, of course, was devoted, loyal, obliging, self-sacrificing – the kind of slave who let Welles do much of his own lighting. But he was no Gregg Toland.

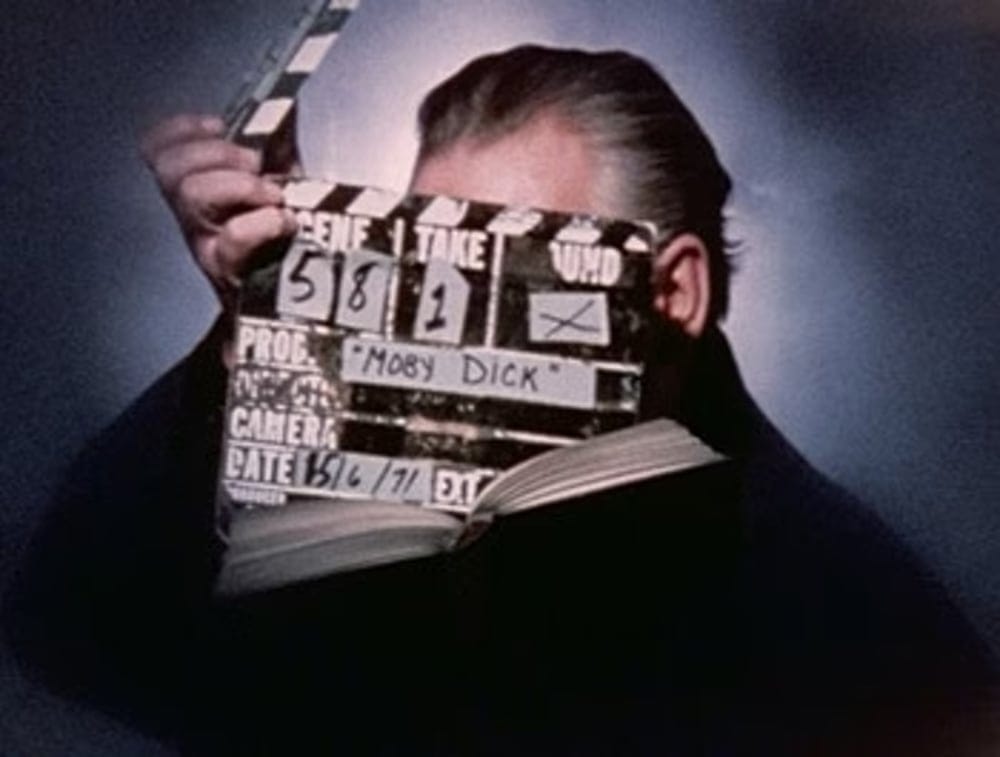

By 1971, “The Other Side of the Wind” was being shot, much of it in Carefree, Arizona. John Huston arrived and was magnificently unfazed when he found there still was no script, only speeches on pieces of paper. But he did not have to learn these, Welles said, it was enough to read them and come up with talk of his own, approximating the material.

Huston, who had been like a character most of his life, stood there in the light and did his best, assured by Welles he was in no way playing a version of himself for Orson. When Huston had a conversation to do, he was told the other person in the scene would be, or had been, Lilli Palmer. Huston was amazed at this, but, valiantly, did as he was told.

They were in Arizona for several months. There were kids doing elaborate catering, and there was Welles, in a purple robe, either lost in thought amid the turmoil of the set or bellowing that he was to be trusted and obeyed. All manner of talent came and went: Susan Strasberg, who played a spiteful film critic based on Pauline Kael; Welles’s friend Peter Bogdanovich; Rich Little; Edmond O’Brien; Cameron Mitchell; Paul Stewart; Mercedes McCambridge; and Oja Kodar, who managed to have better clothes, make up and scenes than anyone else.

There was filming later on in the San Fernando Valley – McCambridge recalled a scene in a yellow school bus inhabited by herself, O’Brien, Mitchell, Stewart and dummies (the point of which she could never grasp). “I don’t see how [the film] can ever be finished,” she said. “Those of us who began it are either dead or unrecognizably older.”

On another occasion, at sunset, McCambridge and Little were to stand side by side against the brilliant sky. It was a shot of their heads and shoulders, but Welles wanted a response to agitation beneath them.

“Why?” asked Little, striving to be professional.

“Why must I be challenged in such things?” Welles roared to the heavens. “I need your shoulders to be still, your hips to sway ever so slightly, a rocking on your heels that is barely noticeable, all of this will give me effect I need with the midgets that will be milling around your feet.”

“What midgets, Orson?”

Welles was too weary to answer, but a crew member quietly confided to the actor: “Mr. Welles says he’s going to be shooting them in Spain next month.”

It was filmmaking out of any control, subject only to the director’s will and whims. Who knows if there was ever anything like a script? Who knows how much was just the spur of the moment? But much footage was shot, and Welles was even seen editing it. The project acquired a producer. It stretched into the late 70s. welles and Kodar were said to have put $750,000 of their own money into it.

And there were other investors: a Spaniard and a French Iranian group headed by the Shah’s brother-in-law. But the Spaniard would end up pocketing the money, and Welles saw none of it. When he was given the American Film Institute’s Life Achivement Award in 1975, two scenes from the picture were shown, and the director used the occasion to beg for completion money. Then, when the Shah fled Iran, all foreign assets – including the film’s negative – were seized by Khomeini’s regime. Welles would die with the footage, its right and prospects subject to that medieval tyranny. The never ending party had turned into never-ending travesty.

For those who have to believe in Welles beyond a reasonable doubt, and for those would like to, “The Other Side of the Wind” is a paradise of possibility. Kodar thought I had great insight – its “shocking” sexuality was probably her doing. But for Welles, the picture was a terrible fantasy inflicted on reality, an imposition to friends and followers. It was a Xanadu – a place no one could go to but no one should forget.

The American movie was doing very well in the late 60s and early 70s. Maverick directors were making fresh, dangerous pictures that whispered to millions about the true, troubled state of the nation: Arthur Penn, John Boorman, Sam Pechinpah, Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese, Hal Ashby, Bogdanovich and Francis Ford Coppola. (Welles wanted to play Vito Corleone in “The Godfather” – “I would have sold my soul to have done it” – but Coppola never considered the possibility.)

All these filmmakers worshiped Welles and took for granted he’d made the status of movie director something to be honored. Nearly all of them remembered the impact of Kane when they were kids. They regarded Welles as a kind of necessary martyr, a Kong who would not perform for the hucksters. They saw that opposition as courage and integrity – it was not yet possible for them to know the helpless rebellion that had taken Welles away.

With so many luminaries aware of his legacy, the Motion Picture Academy in 1970 decided to grant Welles an honorary Oscar for “superlative artistry and versatility in the creation of motion pictures.” He was very touched but chose not to attend. He said he would feel foolish. So John Huston accepted on his behalf and Welles sent a clip “from Madrid.” “Good night, Orson, where ever you are,” said Huston at the Oscars, pretty sure that he was only a few miles away, watching on television.

The glory did not abate. The journal Sight & Sound polled critics and found not just that Kane was still the top film of all time, but that Ambersons now placed eighth in the top 10. Then in 1971, first in the New Yorker and later expanded in a book, Pauline Kael published “Raising Kane”. She was not, evidently, an enemy of Welles. In her review of “Chimes at Midnight,” she pointed out that “the one great creative force in American films in our time, the man who might have redeemed our movies from the general contempt in which they are held, is ironically – an expatriate director whose work thus reaches only the art-house and audience.”

In the years following that review, Kael’s stature had changed. She was now the most dynamic and influential movie critic in America, and “Raising Kane,” it turned out, had a thesis that easily concealed her admiration for Welles: Herman J. Mankiewicz had really written the movie, and Welles had tried over the years to steal credit for it and always been someone who needed writers and other brilliant collaborators. Kael had talked to selected sources; it emerged that she had also resisted talking to Welles, or his other close associates. So the appearance of research behind “Raising Kane” was misleading. Yet it helped give substance to the belligerent tone and the air of exposure.

There was a germ of truth to it all – Mankiewicz was a smart writer, with shrewd insights into Welles and his crafty vanity. But the bias in Kael’s approach blinded her to the ample evidence (later detailed by Bogdanovich and others) of how much Welles had contributed to the scenario. And it did not pay much attention to how modestly Mankiewicz and Toland had fared without Welles. The essay seemed calculated and less than conclusively accurate.

“Raising Kane” was a prolonged controversy. It brought out many defenders and only multiplied the number of times Kane was shown. Welles was injured, but that was good for him: It pierced the somber dignity that was a larger wrap than his cloaks; he was “relevant” again. And glamorous: How much more magic might there be in extra hints of fraud, misanthropy, charlatanism and melancholy?

The best evidence of that is the last picture Orson Welles completed. Backed by a French Company, L’Astrophore, “F for Fake” is flawless and astonishing – unlike anything anyone had ever done. Eighty five minutes of adroitly juggled reportage, fiction and documentary, the film is a reverie on art forgery, scams, practical jokes and the constant possibility of fraud. It involves Picasso; Clifford Irving and Howard Hughes; a great forger of famous paintings, Elmyr de Hory, and that celebrated perpetrator of public outrages. Orson Welles as narrator and on-camera guide. It is the lightest, wittiest film he would ever make. Released in the wake of Watergate, it is also a confession that warns us to trust nothing.

Welles painstakingly edited the film. In his later years, there are stories and tableaux of him in basements and hotel suites surrounded by Moviolas – like a circus maestro with a semicircle of adoring lions. In the windowless gloom of the editing room, he could work forever, talk back to the images, make them the obedient slaves of magic. That pose is evident in “F for Fake,” and it marks a transition in Welles the movie stylist.

In Kane and especially Ambersons, he’s loved extended takes and their unbroken ventures through space and time. But “F for Fake” is driven by montage, fragments (essentially unreliable) put together in the lovely, persuasive rhythms of manipulation. In other words, Welles had taken on a growing awareness of film as fraud.

“F for Fake” was made in 1973 in the immediate aftermath of “Raising Kane,” as was the first attempt at “The Other Side of the Wind.” But if that misbegotten project is helpless proof of all Pauline Kael’s worst suspicions, “F for Fake” is the droll retort. Her attack had freed Welles, and, once exposed, he flowered. That might have been predicted – after all, he was a trickster. He had lied with “War of the Worlds;” he had wondrously confused fact and fiction in Kane.

It comes to this: Welles had read Kael and seen the light at the end of his own tunnel. Nothing else redeemed the futility he had seen and felt since Kane. F for Futility, F for Fate – and F for Fuck Off. The exhilaration of “F for Fake” came from the discovery that there is no higher calling than being a magician, a storyteller, a fraud who passes the time. This is the work in which Welles finally reconciled the European-intellectual aspect of himself and the tent-show demon who sawed cute dames and wild dreams in half. For it can be very hard to live with the belief that nothing matter in life, that nothing is solid or real, that everything is a show in the egotist’s head. It loses friends, trust, children, home, money, security and maybe reason. So it is comforting indeed, late in life, to come upon proof that the emptiness and trickery are in themselves valid and sufficient.

Finally, if “F for Fake” is exhilarating, it is also because of Oja Kodar. She is the naked lady who makes a monkey out of Picasso in its climax. She is more than Welles’s accomplice and model, though – she seems to be his friend. Early on at the railway station, as Welles, in black clock and black Spanish hat, does elementary magic for a little boy, she is there, in furs, to say, “Up to your old tricks again, I see”. It is a sweet, generous moment – a woman in his work was never so natural, so kind or life enhancing. Kodar relaxed Welles, took the edge off his misogyny and made his gazing eyes innocent, sexual and unashamed. We feel happy for him.

“F for Fake” blows Welles’s cover for a world smart enough to see. He knew it was a new kind of film. It could have secured a new future. But the world missed that; “F for Fake” hardly played. No one much noticed the warmth, the fun or the sexiness. He was safe: He was still that famous failure, Orson Welles.

In 1974, he came back to America to be on call for the L.A. talk shows that wanted him. He bought on the edge of Las Vegas, and there parked Paola and Beatrice. But he really lived in the Hollywood Hills, more or less with Oja, though she was definite about maintaining her independence. He became a famous public figure, an inescapable monument to himself. He got into the habit of lunching at Patrick Terrail’s Ma Maison – became, in fact, a reason for going to the place. He had his own table and could be beheld, drooping over a chair, often in the company a small poodle, Kiki. He was on show in a city that prizes leanness above most things. He did his best.

Like anyone weighing 350 pounds, he had back trouble and high blood pressure. There would be diabetes and heart trouble very soon. He stopped drinking – and drink had been energy for him. The laugh became thinner and creakier without booze. The cigars were more and more props instead of pleasure. But he had to stay cheerful and seem robust. He had to laugh at a Burt Reynolds joke about his size and smile on that insecure actor so Burt would not give up on him. Reynolds was big then – even a meal ticket for Welles. A poodle, Las Vegas and Burt Reynolds: Is this hell?

He was a parody of being busy, public performances and private dreams. He was doing commercials for just about any product that asked; he was always on “The Tonight Show” and Merv Griffin; he would narrate documentaries (so long as his contract made clear he never had to look at the picture). He was an actor still, with Pia Zadora in “Butterfly” and in some of the Muppet movies, talking to the animals.

There was another ongoing project, “The Magic Show,” current for at least 12 years of his life. Welles was collecting old tricks, making reflections on the nature of magic and throwing in as many other ideas as he could think of. Burt Reynolds and Angie Dickinson were, from time to time, participants in the film, pieces of which were shot over the years as money and studio space became available. On one occasion, Welles and Dickinson posed for a photograph that is touchingly comic. Welles, in a dark suit and untucked black shirt, is sitting in what looks like a sort of electric chair. There is a cigar in his right hand. Dickinson is doing her best to stay on his lap, but the stomach is so far-reaching, there in not enough lap. So the slender actress leans back against him, perched on one knee, and throws her arm around his neck to avoid falling over.

Loneliness dominated, no matter that Welles was so often at the head of the table or in the chair on a talk show to which all other were turned. He knew “everyone” yet kept only a very few friends.

Robert Kensinger was a young movie enthusiast who went to work for Welles in 1978. Welles lived then on Wonderland Avenue, off Laurel Canyon, “renting”, according to Kensinger, “a crummy little tract house – such a shabby, unemotional piece of architecture.” The garden was littered with Macanudo cigar butts. The interiors were cramped. His bathtub was full of old books. His closet had maybe 30 identical black silk shirts. The place “felt almost like a hotel room. He didn’t do anything to leave a personal mark.”

Welles often sat in the dark in a lounger watching television – but rarely seeing movies. When out in public, he didn’t drink and ate carefully. But at home there were binges.

Kodar kept a room in the house. They did a lot together, but she wasn’t always there. Kensinger could see their fondness, and he believed there was no other woman in Welles’s life, but he said, “I think his sex life was essentially over.”

There was another young man, a valet whom Welles hated but endured. Once, Kensinger observed Welles asking the kid to get him a pair of scissors.

“Why?” asked the kid insolently.

“So I can stab you,” said Welles.

He had become friends with Jaglom, who had cast him in “A Safe Place.” Jaglom was an independent filmmaker: He made films usually with his own money, then sold them himself – very shrewdly. He adored Welles and treasured his sweetness. They often lunched together, and Jaglom began to keep tapes of those occasions – for use someday in a book. Jaglom did all he could to encourage the older man and help his career. In return, Welles gave Jaglom advice: “Never need Hollywood. Don’t let anybody tell you what to do. And never make a movie for anyone else, or on some idea of what other people will like”. It was Jaglom who facilitated a meeting between Welles and Barbara Leaming, who would become his official and very generous biographer. And it was Jaglom who urged him into a project called “The Big Brass Ring.”

The film has never been made. Four years after Welles’s death, Gore Vidal – a friendly acquaintance who often invited him to dinner only to get some last-minute excuse (an early night before tomorrow’s dog-food commercial) – wrote an appreciation of him for the New York Review of books, which concluded with a tribute to the script for “The Big Brass Ring” (“Plainly [Welles] at the top of his gliterring form”).

The script had been published, modestly, in 1987, as a work by Orson Welles “with Oja Kodar”. It has an afterword that recounts the efforts made by Welles and Jaglom to get the picture made. Allegedly, there was $8 million for it with Arnon Milchan to produce. All that was needed was a big star to play the lead of Sen. Blake Pellarin, a man of presidential timber – or perhaps just made of wood. Six actors were offered the chance for $2 million: Warren Beatty, Clint Eastwood, Paul Newman, Jack Nicholson, Robert Redford and Burt Reynolds. All declined. Jaglom takes that as the last evidence of the crassness of the Hollywood system and a virtual conspiracy to ensure the “failure” of Orson Welles.

On the other hand, decisions not to play Blake Pellarin seem to be evidence that one can be an international icon without losing all reason. “The Big Brass Ring” is as bad as anything Welles ever did or attempted. The script is one more lame try at the thriller genre. Quite swiftly, the action confronts Pellarin and Kim Menaker, a disgraced Roosevelt aide who is homosexual. Welles was to have played Menaker, but Orson was not gay – he couldn’t conceive of loving any other person. So we are left with just the romance he felt for himself, and the pathetic discovery that Menaker had kept a handkerchief, starchy from the ejaculate of his fantasizing over Pellarin. When Pellarin learns of it, the script asks him to utter a “sudden, terrible groan.” That was not what Beatty, Redford, Newman, Nicholson, Eastwood or even Reynolds had been looking for.

The long, doleful dialogues between Menaker and Pellarin are grotesque versions of the great make battles in Welles’s earlier work. “The Big Brass Ring” should never be forgotten – or abandoned – as a vital, illuminating footnote to the real egotistical drama and despair of Kane.

Welles kept on, even if now he needed a wheelchair at airports. He played a significant and charming role as a wise old man at the back of the theater in Jaglom’s “Someone to Love,” which would prove a gracious farewell. There was so much not finished: Ambersons, “The Deep,” “The Other Side of the Wind,” “The Big Brass Ring” – even “It’s All True” (in 1985, it was reported that more than 300 cans of the film had been found).

He was doing more work on “The Magic Show” in early October of that year. Barbara Leaming’s book, “Orson Welles: A Biography,” had just been published. He liked it, and why not? It was broadly accurate and very fond. He and Leaming had enjoyed good times together, and the book benefited enormously from his easy, flowing talk. It would have been meanspirited to check everything he said.

On October 9, he was on “The Merv Griffin Show” with Leaming, doing some light magic and helping promote the book. He did not look well – but he hadn’t ever really looked well. Magnificent, yes. But well?

He went to Ma Maison for dinner and then home. He seems to have done some work on the script for “The Magic Show.” But he was there in the house, alone, with no one to hear or report, when a massive heart attack killed him.

Had he lived, he would have been 81 this year. But the living was no longer much fun for someone who had been one of the great American hedonists. He was wry enough to know he needed to die, or vanish, to be recovered. And now he is everywhere – in biographies, in TV documentaries, in attempts to rescue the lost films. All of a sudden, his own America seems to realize that here once was a genius. Like Kane’s survivors, we can’t stop thinking about him.

It’s as if he is up to his old tricks, even directing our thoughts. Do we regret never really telling him how much he meant? Do we care anymore that he behaved badly? Or is it easier for him to be a dreamer who has us in his sleep, eager again to be seduced by that magical, utterly bogus voice: “Ladies and gentlemen, this is Orson Welles.”